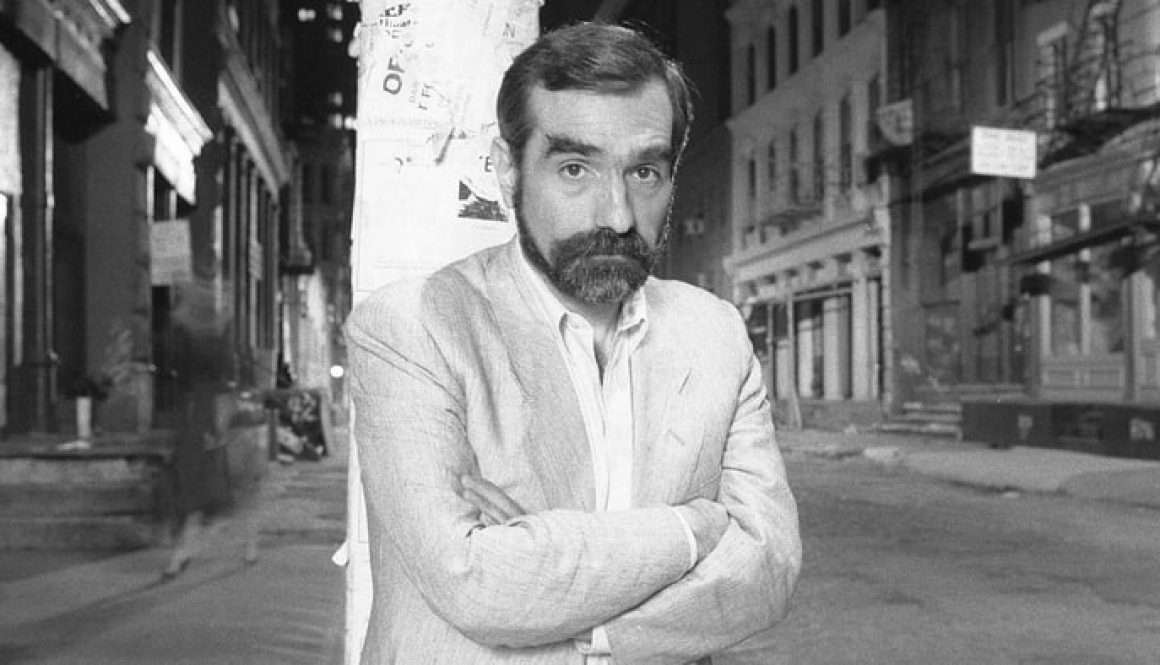

Sexual Politics & Gender in Martin Scorsese Films

“How’s your wife?”… “She’s still alive, so my life is fucked. You know?”

– Donnie, The Wolf of Wall Street

The question of sexual politics and the notion of gender within the world of film is notorious; Martin Scorsese’s body of work is no exception to this. Reflecting on his auteur approach, a term deriving from the French film publication, Cahiers du cinema and coined by their film critic Andre Bazin, Scorsese’s main focus much like any other ‘auteur’ filmmaker is keeping true to his beliefs and his way of filmmaking; pleasing the crowd and seeking critical approval is not. Like Scorsese, other auteur-driven filmmakers give you a piece of their mind and an insight into their thoughts through the medium of film. In discussing Scorsese, I intend on critically exploring and examining the issues of sexual politics and gender raised within his body of work. I will demonstrate this within his films Raging Bull (1980), GoodFellas (1990) and The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) whilst referencing other films of his and his influences.

Born and raised in the 1940s, in the Little Italy section of Manhattan, New York by Italian immigrants, Scorsese’s body of work addresses his Italian-American identity, and his Catholicism beliefs of the concept of guilt, redemption and family which he was raised upon. Whilst also his familiar themes of masculinity, modern crime and internal gang conflict influence his moviemaking style and stories. Though it is the overarching idea of masculinity, male dominance and submissive females characters within the body of language which forefronts the authorship of a Martin Scorsese feature. In discussing this, it can be argued Scorsese’s masculinity theme derived from his childhood, growing up in an Italian-American neighbourhood in isolation due to his horrid asthma, meaning from a young age he was unable to run and play sports, leaving him to watch the other kids from the indoors and instead form an emotional bond with 1930s, 40s and 50s Western cinema.

Yet, of course, there are a number of contributing factors to Scorsese’s idea of masculinity, sexual politics and gender which can be traced back to his influences in film. Italian Neorealism, Western classics and the French New Wave were heavily featured in Scorsese’s early childhood; William Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931, Wellman), King Vindor’s Duel in the Sun (1946, Vindor) and Elia Kazan’s On The Waterfront (1956, Kazan) feature dominant male characters and control the nature of the film in terms of their masculinity embodiment, their relationship with female characters and the stereotypes they emphasise within the historical background these stories are set in.

These traits are depicted throughout Scorsese’s catalogue, from his inaugural debut into the world of mobsters and masculine dominant males, with the 1964 short It’s Not Just You, Murray! (Scorsese, 1964), with the ending’s distinct inspiration originating from Federico Fellini’s 81/2 (1963, Fellini) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960, Godard), the realism element portrayed. His use of the generalisation of Italian-American population in his films form the basis of his stories, with the realistic nature of their personality, conversations and mannerisms all present in his popular features. Scorsese discussed this in an interview with the publication the “New Statesman,” how he recognised himself in Ray Liotta’s personality when casting for GoodFellas; growing up on the streets of Little Italy, keen to avoid the children on the street, using his quick wit as a means to escape trouble. As Scorsese explained, ‘It’s what I thought of these guys when I was six.’ (Shone, T. 2014, New Statesman) [Online].

In discussing the notion of Italian-American in Scorsese features, the family aspect takes a considerable role in his stories. They are central to his emotionally distant narratives with the idea of the ‘family’ being the priority for each character, and help formulate a backbone to his stories which reflect his own experiences in life. An example of this is after brutal beating of “made man” Billy Batts in GoodFellas. Henry helps Tommy and Jimmy dispose the body in a barren wasteland, but not before they have dinner at Tommy’s [Scorsese’s] mother, in which they are respectful and gracious to her, a far-cry from the violence shown moments earlier. Yet, in reflecting Scorsese’s personal experiences, when GoodFellas lost the academy award for “Best Picture” to Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990, Costner), the thing that hurt him the most was putting him ’in the front row with my mother, and then [he] didn’t win’, (Shone, T. 2014, New Statesman) [Online], this is seen as a sign of disrespect in the Italian-American culture.

Yet, in examining the issues of sexual politics and gender, Martin Scorsese has been often criticised for his portrayal of Italian-American males in their approach of sexism and womanising female characters. In his black and white boxing feature, Raging Bull (1980, Scorsese) which established Scorsese’s auteur status, is set in an Italian neighbourhood in the Bronx, New York during 1941. It follows Jake LaMotta (Robert Di Nero), an Italian-American boxer and his personal trainer/brother Joey (Joe Pesci), as they climb to the top of the boxing world. It views Italian-American males as loud and aggressive characters who have a total disregard to women, as illustrated within he first five minutes of the film when Jake is seen flipping over a table and shouting at his then-wife and through crockery at the wall, over how she overcooked his steak.

Much like Jake and Joey LaMotta in Raging Bull, there’s a consistent theme of the charismatic relationship between men, or a “bromance” amongst Scorsese’s main male characters, which refers towards Scorsese theme of masculinity; Jordan and Donnie in The Wolf of Wall Street, James, Henry and Tommy in GoodFellas and Jesus and Judas in Scorsese’s biblical story The Last Temptation of Christ (1988, Scorsese). There is a sense of male community amongst these characters, all working towards their individual salvation through self-knowledge and the search for self-awareness without the need of women, which, in the case of The Last Temptation of Christ has transcended through biblical times into the twenty-first century, displaying a universal and life-spanning theme of masculinity and male community. This is in comparison to Scorsese depiction of women within his body of work, and the lack of a community portrayed amongst them. They are predominantly shown to be by themselves, without a relationship with another female character for the most part.

However, in one of the few cases we witness a sense of a female community in during GoodFellas with Karen. In her scene with the other married women gossiping about ‘friends’, we see them joking amongst one-another about people and situations, even though Karen doesn’t like it she takes part to feel she is part of the ‘community’. Yet, this scene shows women are weak as Henry’s voiceover is heard over it saying, ‘Saturday nights are reserved for the wives and Fridays for the girlfriends’, which contribute to the undermining of women within this film, displaying their role in the household and bringing up the children is not as important compared to what they do, details and the constant cheating men are involved with. Whilst the use of voiceover infers the ‘voice of god’ cinematic technique, predominantly used by documentarians in an effort for the persons voiceover to be seen as the bearer of truth and controller of the narrative.

Additionally, women in his films a characterised as weak, inferior characters in comparison to the men, whose only purpose in the narrative is to be told by their husbands what to do; reflecting a parent-child relationship. An example of this when Joey and Jake are discussing the future of Jake’s boxing career, when Joey’s wife makes a passing comment, to which Joey replies ‘Who asked you?,.. When people are talking, you don’t interrupt. It’s none of your business. Get outta here, and take the baby with you’. This reiterates Italian-American men in his films are often shown treating their wives poorly. Also, we are shown physical abuse inflicting on them, as shown in the cases of Jake’s wife, Vickie LaMotta, Henry and Karen in GoodFellas and Jordan and Naomi in The Wolf of Wall Street.

Finding its place among the New Hollywood’s classics, Raging Bull confines itself to the generalised sport convention of focusing on the male body, it ‘presents the powerful male body as an object of desire and identification’ (Cook, 1982, p.43) through the use of slow motion, which Scorsese frequently uses throughout the narrative to heighten tension and exploit sexuality. This technique also manifests itself through Scorsese’s male gaze exploits, when Jake’s eyes are fixated on Vickie at the public pool. The camera ever-so-slowly zooms in on Vickie for a number of seconds, until she become to dominant figure in the scene. As Cook states, the audience see Vickie ‘entirely through Jake’s eyes’ (Cook, 1982, p.43), we are intended to feel the same as Jake, an attraction to her, as the Scorsese only limits her to seen through ‘actions, dialogue, and Jake’s dialogue’ (Hayes, 2005, p.94), this is was we perceive her to be, purely for aesthetic reasons. Later, the use of slow motion appears again with Vickie greeting and conversing with her other male friends. The slow motion here is used as a device to aid the audience in understanding Jake jealously.

This idea of the “male gaze,” derived from the film theorist Laura Mulvey, and her 1975 essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she argues Hollywood studios and directors often force the audience to watch their film from the male perspective, provoking them to identify women in the film as an object of desire, is most evident in Martin Scorsese’s latest feature, The Wolf of Wall Street (2013, Scorsese). Naomi is presented as a one-dimensional character, whose only purpose in the narrative is also for purely aesthetics, as Scorsese shows her in multiple revealing outfits in order to further emphasise the attractive appeal she displays as a “trophy wife”. It could be argued that Naomi and the other female characters/extras within the film are seen through the perspective of Jordan Belfort, and much like Jordan first wife Teresa, as disposable objects. This is evident through the amount different of women Jordan has sexual encounters throughout the story.

Despite this, Naomi, along with Teresa, his Aunt-in-law Emma and Karen in GoodFellas, are portrayed as intelligent women, using their voice of reason and sexuality for their advantage, almost femme fatale-esque. Naomi, Aunt Emma and Karen are all involved in some form of illegal activity, stemming from the main protagonists job. As a result of this, much the male protagonists in his films, women too are viewed as being powerful and as much corrupted as the men. These women within Scorsese features can stand up for themselves, by inflicting physical and verbal abuse towards their husbands in an effort of displaying their anger to them. An example of this is Naomi arguing with Jordan over calling for another women in his sleep, so she withholds sex as a punishment, and Karen shouting at Henry over missing their date and later-on pointing a gun at Henry whilst he is asleep, threatening to kill him because she thought he was seeing another women.

Richard Rushton’s point of the potential celebration of criminality in Scorsese films further expand on this point of corruption not being identified with a certain gender, he states ’in the final account, the hero and the villain, good and evil, can barely be told apart’ yet somehow ‘Scorsese manages to offer some kind of barely breathing ‘life support’ for the notion of a good America’ (Ruston, 2012, pp. 131-132). This idea of offering ‘life support’ to America could also be tied into the women e.g. Naomi and Vickie within Scorsese films leaving the man e.g. Jordan and Jake, offering a form of justice in that they are left loveless. However, on the contrary to this, each character within Scorsese’s body of work is left alive, unharmed and better off than they were first shown to the audience with still either having a job or money, leaving a juxtaposition for the audience to determine whether they have atoned for their sins.

In-keeping with Scorsese’s view on women, there are strong, independent women who are dominant in the narrative, this is the case for Scorsese final feature with De Nero and Pesci, Casino (1995, Scorsese). Scorsese shows Ginger to be a strong female character who is independent, with the quote of Ginger saying: ‘I’ve been independent my whole life, I haven’t had to ask anyone for anything’. This idea of independent women is also shown in Scorsese’s 1974 film, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Scorsese, 1974), in which the story focuses on a single mother’s journey and effort to protect her child from violent men, whilst attempting to earn her own money from a potential singing career. Despite this, when Karen utilises the voiceover in GoodFellas, presenting her to being powerful by taking control of the narrative and utilising the “voice of god”, she confesses how her then-boyfriend’s (Henry) gun is attractive to her, meaning Scorsese is undermining her through sexual contexts; ‘I know there are women…who would have gotten out of there the minute their boyfriend gave them a gun to hide. But I didn’t. I got to admit the truth. It turned me on’.

Issues of sexual politics and gender are consistent theme in Martin Scorsese films, they are presenting in the majority of his gangster filled stories in one way, or another. This can be marked by his multiple collaborative relationships which originated in his earlier films. His editor, Oscar winner, and powerful women in the film industry, Thelma Schoonmaker first worked on his 1969 film Who’s that Knocking at my Door (1969, Scorsese) and has edited all his films since Raging Bull, whilst cinematographer Michael Ballhaus has been a regularly member of his team, with screenwriters Paul Schrader and Nicholas Pileggi contributing to his stories, as well as actors Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio starring in his most known films. Though during his forty-plus year span of filmmaking, his evolution of duality between men and women has not changed an awful lot. Generally, the films I have covered are not set in the modern era, they are set predominantly during the 70s, 80s, and 90s, with the exception of Raging Bull. Perhaps this could be a contributing factor to how Scorsese perceives his women, or how each of his films have a biographical narrative, based around on a male character who have had unusual lives.

To conclude, American film critic Andrew Sarris felt the presence of a significant director behind the camera made the art of cinema more personal. Personally I agree with this, Scorsese is ‘true’ auteur; he doesn’t care about the profitability of his projects or the popularity, as shown by The Last Temptation of Christ. Cahiers du Cinema also defined authorship as ‘legitimate,’ how an auteur can create good, and bad films but stick to their themes, cinematic style and the same collaborators. Scorsese captured the violence of middleweight champion Jack LaMotta and his and family in Raging Bull, depicted the rise and fall of ‘wise-guy’ Henry Hill in Goodfellas and delved into illegal-stockbroker Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street and his ridiculous life. His view of gender, sexual politics and general perception of gender can be viewed as his backbone of auteur making, with the underlying masculinity/“bromance” theme, and a general male dominance his films, with women portrayed in less-significantly, submissive state compared to those of the men. Similarly to the themes of another auteur director, Alfred Hitchcock and the well-known “Hitchcock Blonde” theme within his body of work. However, Scorsese’s ideas of sexual politics and gender could be a combination of his Italian-American upbringing, the influences from the directors he watched growing up, or his strict-Catholicism livelihood. Yet these remain an integral part of his auteur style. In my final statement, Martin Scorsese famously said in an interview for the Casino DVD extras, ‘I’m obsessed with the relationship and the dynamics between people and family, which is why women lack in my film. I base my scripts on personal experiences’.

Bibliography

- Cook, Pam. “Masculinity in Crisis? Pam Cook on Tragedy and Identification in Raging Bull.” Screen 23. 3-4 (September/ October 1982). pp. 39-46

- Hayes, Kevin. Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. (Cambridge University: Cambridge, 2005). p. 94

- Rushton, Richard. Cinema after Deleuze (London: Continuum, 2012), pp.131-132.

- Shone, Tom. “Mythical, Merciless Butchness: Martin Scorsese’s Men”. New Statesman, 16 Oct. 2014. Web. 24 Feb. 2015. Website: http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/10/mythical-merciless-butchness-martin-scorsese-s-men

References

- Raging Bull, 1980, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- GoodFellas, 1990, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- The Wolf of Wall Street, 2013, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- Casino, 1995, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, 1974, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- It’s Not Just You, Murray!, 1969, Dir. Martin Scorsese. (Film)

- The Public Enemy, 1931, Dir. William Wellman. (Film)

- Duel in the Sun, 1946, Dir. King Vindor. (Film)

- On The Waterfront, 1956, Dir. Elia Kazan. (Film)

- Dances with Wolves, 1990, Dir. Kevin Costner. (Film)